# Seb on Software Engineering Management

Edited

I recently started being a manager. It's at a small company and I kind of had to figure it out myself; here are some of the things I've learned.

# Leadership

# Communication

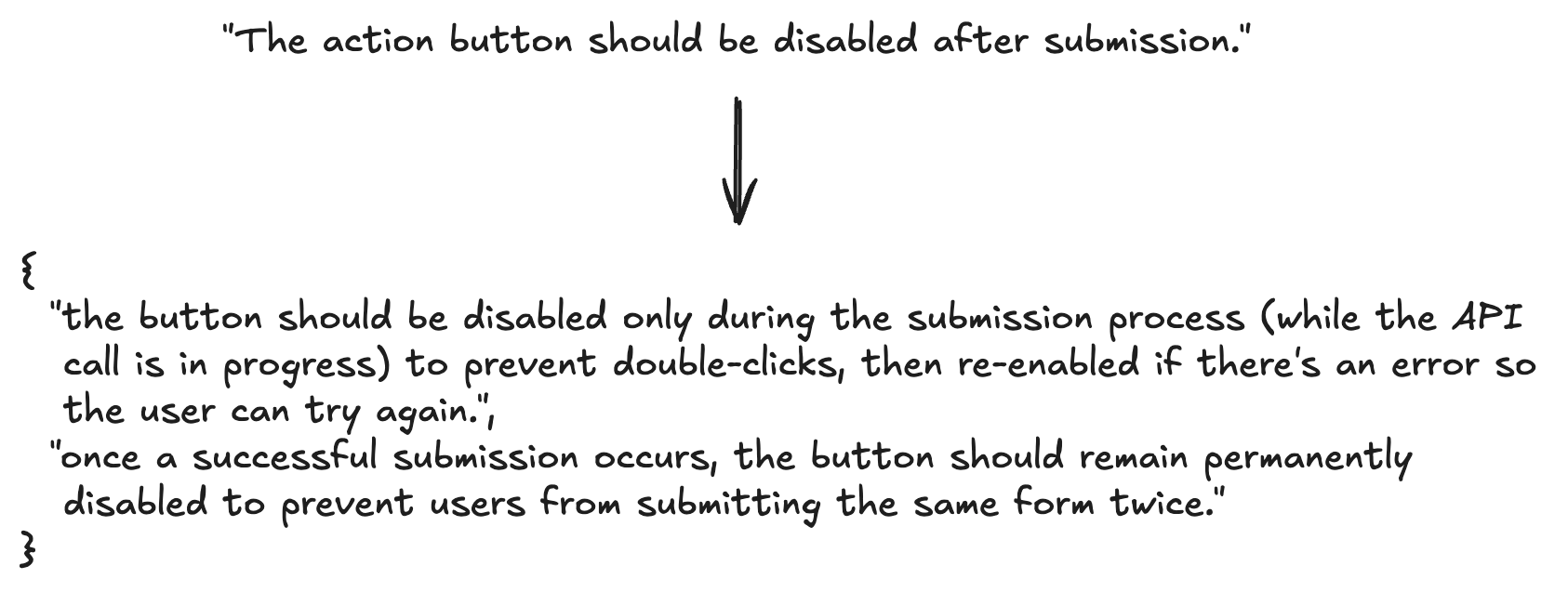

When you say a thing, your words map to a set of interpretations the listener could have based on their context. Your words are "clear" when that set has only one element.

# Trust

Everything is easy when you're operating in a high-trust environment, and everything is unnecessarily difficult in a low-trust environment.

In a high-trust environment:

- People are happy and productive.

- People trust each other's technical decisions. Therefore, there's less decision-by-committee.

- People have less Fear Of Looking Dumb (FOLD), and therefore ask more questions.

- People are more likely to give feedback early and often.

In a low-trust environment:

- People are unhappy and unproductive.

- People don't trust each other's technical decisions. Therefore, everything goes through decision-by-committee.

- People are afraid to ask questions. Therefore people make mistakes that could have been avoided.

- People are more likely to quit and/or get fired.

Among your highest priorities should be ensuring that your team is a high-trust environment.

To increase the "trust level" on your team, create opportunities for positive-sum shared experiences. Generally speaking, when team achieves its objectives, trust improves.

Here are some specific things that have worked well for me in the past:

- Work in-person, and physically colocate the desks for your team.

- Look for and surface shared non-work interests (e.g. anime, video games, sports, music, etc).

- Spend time identifying the small "annoyances" or "discomforts" people have but aren't vocalizing. For instance, one member of our team was feeling cold in the office, so we got a space heater they could put under their desk. Doing this shows that you care about them as people, and therefore, they're more likely to open up and start trusting you and the rest of the team.

- Do fun things during off-hours or schedule weekend outings where members can get to know each other in a non-work context. For instance, at SFC we recently got a switch, and after-work smash became a routine activity that has a very positive effect on the company-wide trust value.

- Factor this into your hiring process - even if someone passes technicals with flying colors, if they're unlikely to "mesh" well with the rest of the team and feel comfortable at your company, it may be worth not hiring them purely on this basis. For instance, if you have a team of "frat bros", hiring a "wholesome muffin" may not be the best move. Similarly, if you have a team of "wholesome muffins", you probably shouldn't hire a "frat bro". This is why you typically want to balance your team out at least a little bit, because if the vibe is too intensely in one direction, it will become difficult to hire people who fit in.

- Invoke Crocker's rules for yourself, and encourage others to do so if they're comfortable.

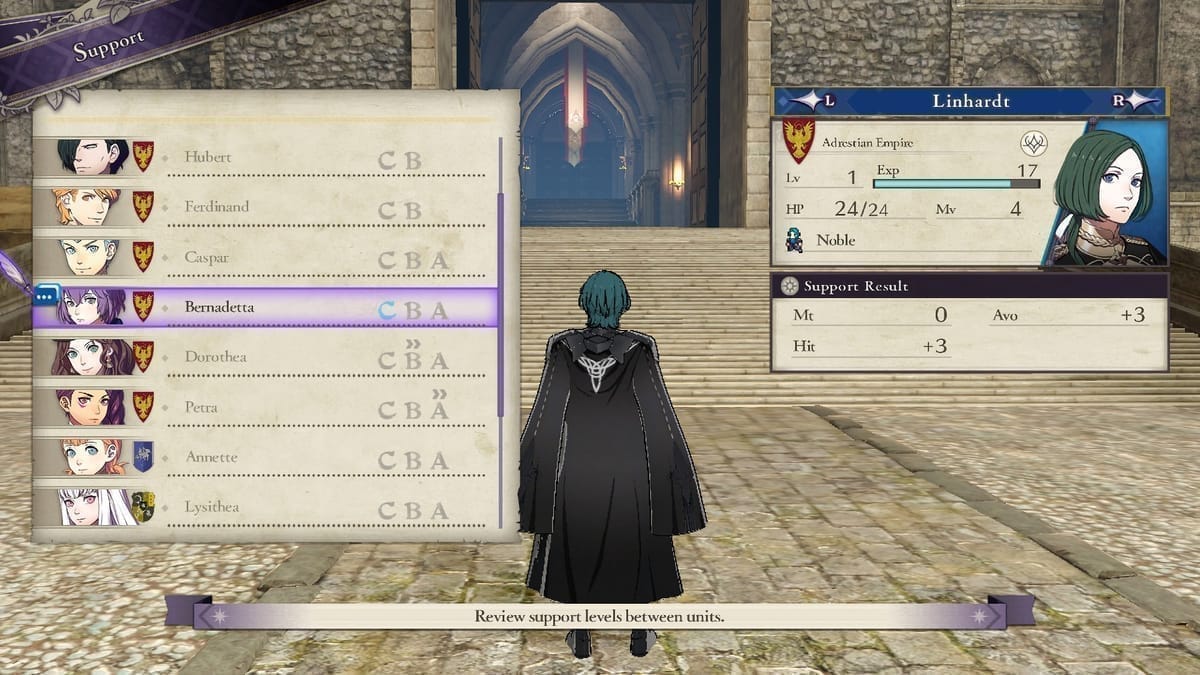

If you've ever played Fire Emblem (any of them), building trust is a lot like increasing the pairwise support levels between characters. I think Fire Emblem is a great analogy for management in general, so if you like JRPGs, I highly recommend playing it.

# Team composition

Everyone has strengths and weaknesses. Everyone has likes and dislikes. Your team is at its greatest when everyone is doing things they like and are good at.

For example, some engineers like to solve puzzles. Others just like getting shit done. Some engineers want to write "beautiful" code. Others just see it as an instrument of business. Each of these is better in some situations than others.

The Fire emblem analogy applies very well here.

# Blame versus responsibility

Build a culture of "responsibility" based on the following maxim: Something can be your responsibility without it being your fault. That is, responsibility is about the outcome and blame is about the person.

This maxim especially applies to you. As a leader, you hold ultimate responsibility for your team. It's very important that you lead by example and take responsibility for mistakes, in particular when they're not your "fault".

This is effectively a different framing of a "blameless culture", placing emphasis on the agency individuals have to solve problems. All of the "blameless culture" stuff still applies:

- All mistakes are a learning opportunity.

- Dwell on solutions, not problems.

- Criticise behavior, not people.

# Hiring

The right time to hire someone is when there's something that you currently do or need to do, but the scope has grown to the point where you can't do it anymore. This will give you a very clear picture of what their day-to-day will be like, which in turn gives you a very clear picture of the "slot" they need to fit and grow into.

Since you're the one currently doing the job, you have the most context regarding the role. Therefore, you should own as much of the hiring process for your team as you reasonably can.

When sourcing candidates, it's more useful to ask the question: "Where is the kind of person I want likely to be?" than it is to ask "What skills do they need to have?". If you search for skills, you end up wasting a lot of time interviewing candidates who aren't what you're looking for. This is especially true when you're working with people like recruiters who don't have an intuition for "what a good engineer looks like". It's better to say "The kind of person I'm looking for is likely to be found on the Android firmware team at Google" than it is to say "I'm looking for a systems programmer".

# Valuing Experience

Experience isn't really something to value in and of itself. It's more of a "proxy" for underlying things that often come with experience. Some things that come to mind include:

- basic engineering practices, like using git, reviewing code, writing docs, and working on a team (really only an issue with hiring new grads).

- niche domain expertise

- engineering taste

- "sage wisdom" - having solved similar problems and/or made similar mistakes.

- a hardened intuition for working at scale

Since many of these things aren't that correlated with "years of experience", I think it's very easy to overvalue experience. Experienced people aren't cheap, and often come with more strings attached (spouse, kids, less willing to relocate, etc.) than a twenty-something will.

Here's a better way to value experience: when you find yourself wanting someone "experienced" ask yourself what it is that this "experienced" person has that you want, and then try to look for that irrespective of experience.

# Interviews

When it comes to interviews, here are some things I believe.

The delivery of an interview matters just as much as, if not more than, its format.

It's important to be intentional about what you select for. Well-delivered algo interviews select for some degree of problem-solving ability, but don't give you much signal on other important things, like:

- How much they care

- What they're motivated by

- How big their ego is

- Whether or not they actually like programming. Oftentimes it's obvious when someone does just from their resume alone.

- Their ability to translate business problems into engineering problems.

- Their appreciation for unknown unknowns and the ability to find them.

- Their capability to find the context they need on their own.

Vibey things like the comfort level with tools of choice, the depth and specificity when discussing past work, and the way the candidate talks about themselves are pretty high signal. Often, within the first 10-15 minutes I can tell whether or not someone's going to end up in the running to receive an offer.

I also think many people overvalue vibes. Vibe checks are quite easy to get past if you're charismatic and good at communicating. While those traits are good traits to have in an engineering hire, they aren't necessarily correlated with technical ability. So it's also bad to entirely rely on it.

Ref checks are very good. They're pretty low effort and quite high signal - you should do them in the final stages when you're choosing a winner from among your best candidates.

# Onboarding new hires

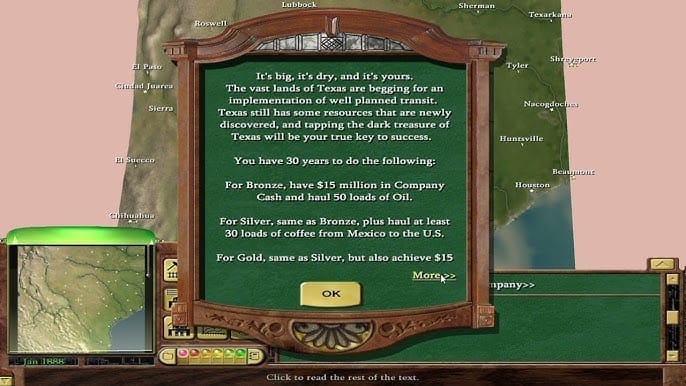

My preferred approach is what I call the "onboarding ladder" - a series of progressively challenging tasks in three categories:

- Bronze: Small with little to no context required. Designed to introduce the new hire to the low-level aspects of the thing they're going to be owning. These will tend to be things like adding logs, fixing low-context bugs, and small refactors improving code clarity. These tickets should be written in the form "here is a thing that should be done - do it".

- Silver: Small with some context required. Designed to introduce the new hire to how things they learned about in the bronze bracket interact with each other. These will tend to be things like fixing small code changes, mid-context bugs, and implementing small features. These tickets should be written in the form "here's a problem, and here's one or more recommended ways to solve it".

- Gold: Medium-size with a lot of context required. Designed to enable the new hire and allow them to demonstrate they have acquired the requisite context to be delegated real things.

The objective for the first one to two weeks is for the new hire to complete a gold-level task as quickly as possible. Once they complete a gold task, they've acquired sufficient context to be considered "onboarded", and they're done with the ladder.

The goal of this exercise is not for the new hire to complete as many tasks as possible. If tasks in the current bracket are too "easy", they should move up a bracket.

A good rule of thumb is that, on average, the new hire should be roughly 50% confident in what they're doing. If it's too easy, they're not learning enough, and they should skip to the next bracket. If it's too hard, they're also not learning enough, so they should drop down a bracket.

As for numbers, I typically assign 5-10 bronze tasks, 3-5 silver tasks, and 1-2 gold tasks.